Please note: this page contains images of human skeletal remains.

Overview:

Since 1996, the Sedgeford Historical and Archaeological Research Project (SHARP) has excavated 291 whole or partial articulated skeletons from Boneyard, an Anglo-Saxon cemetery in Sedgeford, along with significant quantities of disarticulated human bone. A further 126 skeletons from the same cemetery, excavated in the 1950s and 60s, have also been identified in other collections. Post-excavation analysis is currently being carried out on the entire extant population (Faulkner et al 2014:138). From the remains of the ancient Sedgeford people we have learned a great deal about past lives and experiences. The Introduction to Human Remains course delivered by SHARP gave me an exceptional opportunity to learn how to carry out the archaeological interpretation of ancient human remains and prepare an osteological report.

The course covered basic anatomy, determination of age and sex, dentition and paleopathology, as well as recording methods. The ethical aspect of studying human remains and how to interpret population data was also discussed. This allowed me the opportunity to study human skeletal remains using skeletons and disarticulated bones excavated from the Boneyard site. The program was delivered by five experts in the field of osteology over a packed six-day period and we were examined on three occasions on what we had learned. Each test had us identifying various human bones in various states of preservation. We were asked to identify the bone, its orientation, the sex, age, relevant features, and any pathology or non-metric traits. The week was based around the recording of an individual skeletal assemblage, in my case that of skeleton number S1016. To achieve this the week was broken down into a series of lectures, seminars, and practical sessions which mirrored the relevant sections within the osteological report.

Sedgeford Historical and Archaeological Research Project (SHARP)

SHARP is located in the small village of Sedgeford which is in the north west of Norfolk, England. It has been an active research project since 1996 and the excavations conducted there span the Late Mesolithic, Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age, Iron Age, Romano-British, Anglo-Saxon, Medieval, and WW1 periods. The project runs a series of courses over a six week period during the summer. These cover environmental archaeology, archaeometallurgy, non-invasive archaeology, and human remains. More information on the research conducted by the project and the courses offered can be found on their website here. Excavation volunteers and course participants tend to camp onsite and there are numerous facilities available to make the time spent there a family type experience.

Throughout the week, the course ran from 8:30am, after the daily site briefing through to 5:00pm. On occasion, we did run overtime to complete the tasks for the day. The following is a breakdown of the daily activities.

Day 1 (Basic anatomy, bone identification and orientation)

The morning session began by going through the 206 bones of the body. This included the orientation of the bones and the terminology used for specifying the position and direction within the body. We also looked at landmarks and specific bone features

In the afternoon, we were introduced to the human remains recording system we would be using throughout the week. The remainder of the afternoon was given over to becoming acquainted with our assigned skeleton and proper handling procedures.

Day 2 (The development of the human skeleton)

Today we were given an overview of how the skeleton develops from its initial stages through to adulthood. This included discussing bone growth and the estimation of age, sex and stature.

The afternoon was focussed on further recording of the assigned skeleton and a 30-minute test which involved the identification of 10 bones from the Sedgeford archives. We were required to identify the bone, its orientation within the body and at least one surface landmark.

Day 3 (Dentition and Non-metric traits)

The morning session had the group looking at basic dentition and how to record it for reporting. We also looked at how to use dentition to age skeletons.

The afternoon was an introduction to non-metric traits where we looked at more Sedgeford human remains, which have quite a range of non-metrics. We finished off the day with more recording of our assigned skeletons in the context of what we had learned throughout the day.

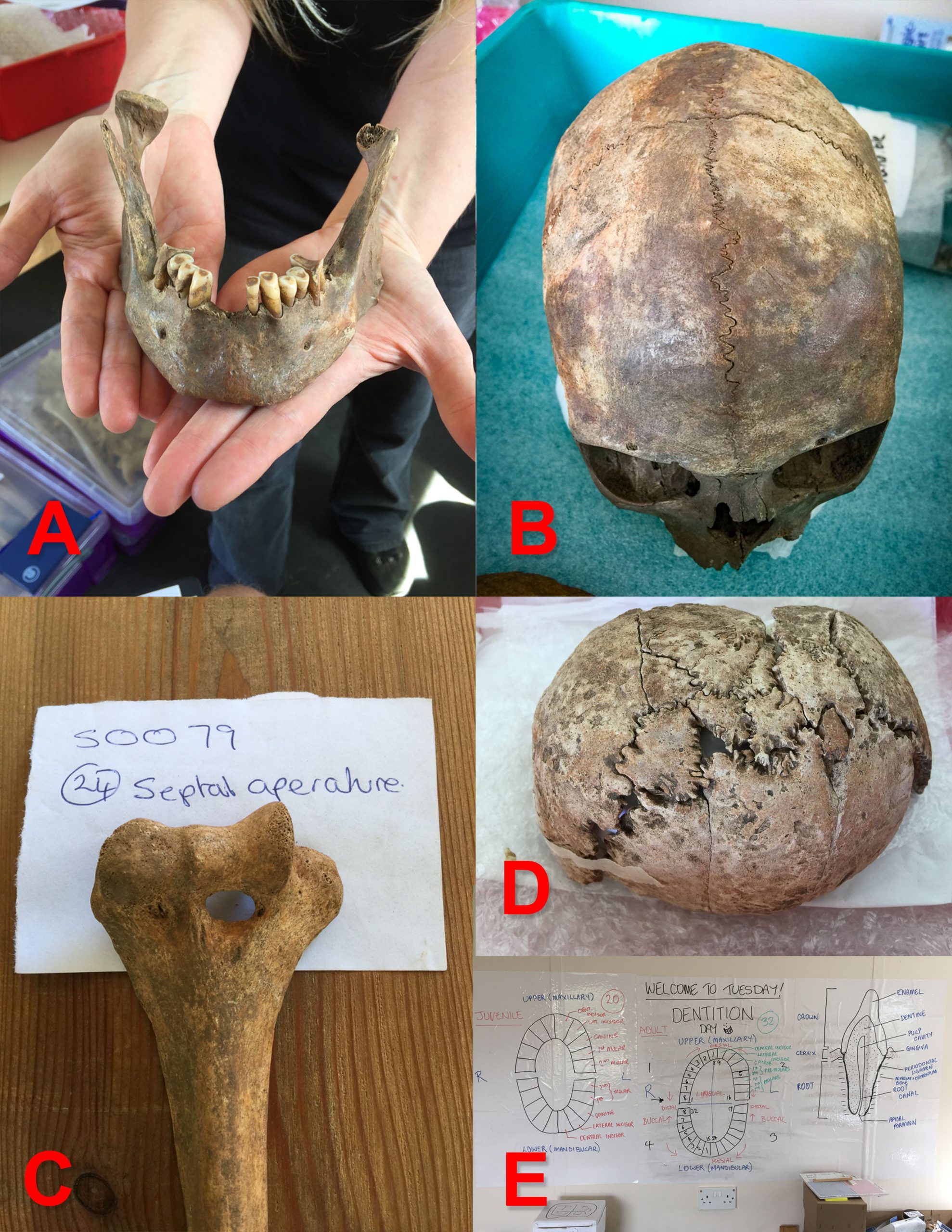

The photograph shows some of the non-metric traits present in the Sedgeford Anglo-Saxon collection. Extreme gonial flaring (A), metopic suture (B), septal aperature (C) extreme ossification (D), and dentition lecture (E)

(photo: P. Docherty)

Day 4 (Pathology)

The whole day was given over to looking at pathology, again using the Sedgeford human remains as examples. We looked at how trauma and disease can affect the skeleton and what can be determined from examination of skeletons and how to record pathology. We finished by recording the pathology of our assigned skeletons.

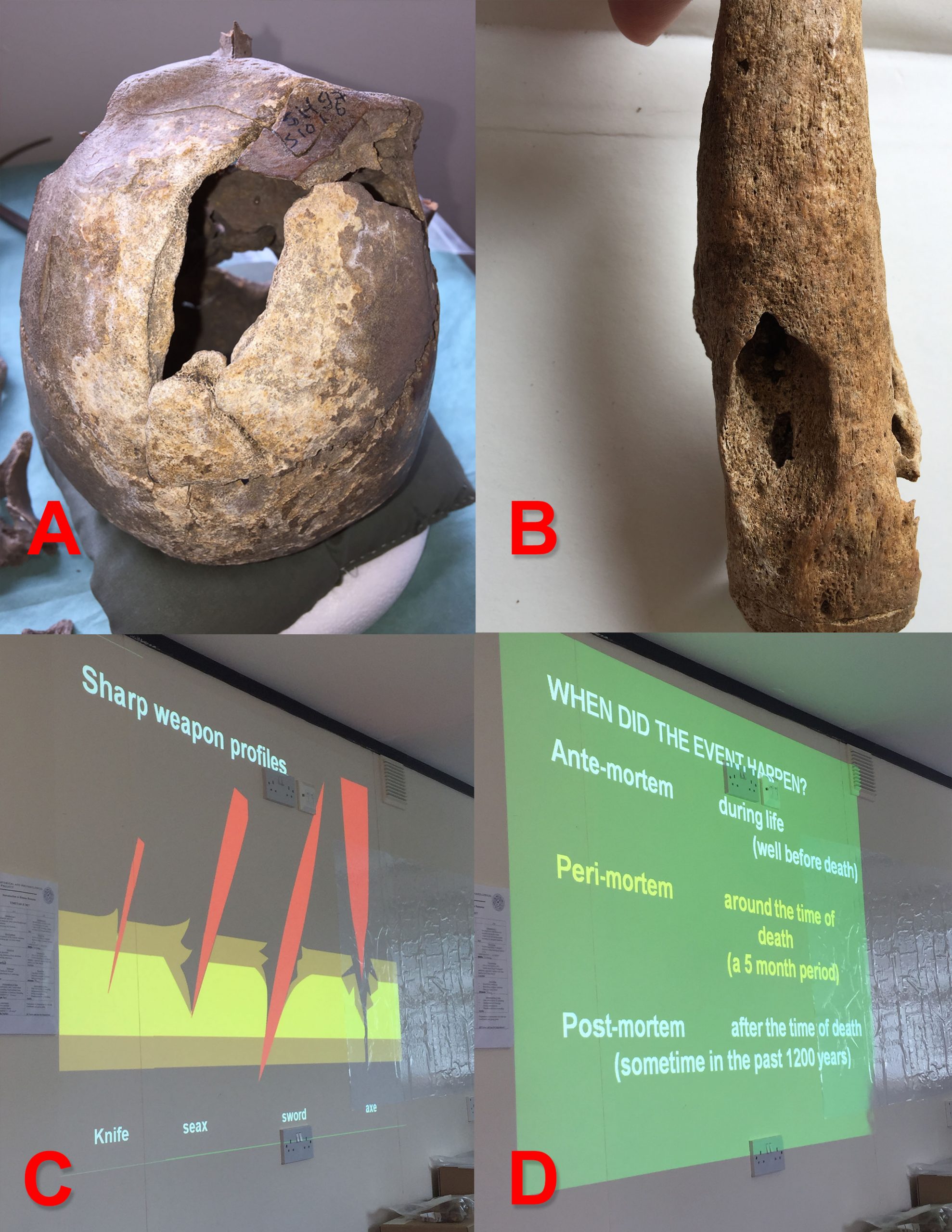

Photos show examples of extreme trauma to cranium (A), severe osteomyelitis on right ulna (B), lectures on pathology (C & D)

(photo: P. Docherty)

Day 5 (Interpretation of data)

This was the final day of recording information about our assigned skeletons but first we had to have another 30-minute assessment like the previous one on Day 2, however this time we had to also identify any pathology and non-metric traits.

Later we looked at taphonomy, conservation, the recording of disarticulated bone, data construction and sampling before completing the recording of our assigned skeletons and presenting our findings to the rest of the group.

The image here shows material for the taphonomy lecture (A), one of the assessment tables (B), and the Sedgeford human remains archive (C)

(photo: P. Docherty)

Day 6 (Ethics and Site Presentation)

The morning was a change from previous days in that we were given a role-playing scenario which highlighted a possible ethical situation that archaeologists can find themselves in. In this instance the scenario revolved around a developer who, during the construction of a road network had uncovered a Bronze age burial. This evolved through the session into an Anglo-Saxon cemetery and how the villagers, archaeologists, and developers had to work together to find a solution which would suit all parties. This was followed by a final 45-minute assessment encompassing all that we had learned throughout the week and the careful repacking of our assigned skeletons.

After lunch, we all had to work together to produce a presentation which would be delivered to the whole site including any visitors. The presentation had each student discuss elements of recording human remains where I finished the presentation with a re-enactment of the possible death of my assigned skeleton using other team members as actors.

Image shows the lecture on burial practices and a demonstration of the wrapping of a shroud (A), the final assessment table (B), the ethical debate session (C).

(photo: P. Docherty)