The focus of this object biography is a folding Victorian silver fruit knife which was recently inherited by the author from his great uncle. The primary intention being to establish when, where, and who made the knife.

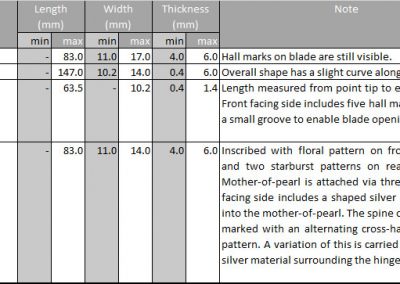

Physical description of the knife

The Chaîne opératoire

Material Resources

Pure silver being too soft for use as a cutting implement, was replaced with sterling silver being 92.5% silver and 7.5% of copper, making it more resistant to wear. Silver is normally found close to lead or copper deposits and whilst sources had been found in England, during the Victorian era however, the main supplies were from North America, Russia, and Australia showing a global trade. The purity of sterling silver has been regulated for centuries in England and the assay offices ensure manufacturers maintain the correct purity and pay the appropriate duty.

Mother of pearl, or nacre, is found on the inner layers of mollusc shells such as the pearl oyster and freshwater pearl mussel. Nacre is a form of calcium carbonate layered with organic silk-like proteins making it a resilient material being tough and crack resistant. It was commonly used during Victorian times for decorative purposes.

Production

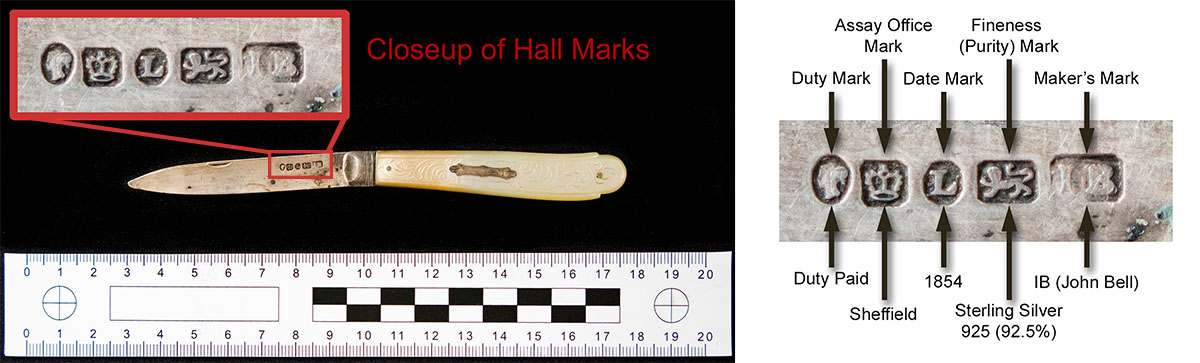

The Silversmith manufactures bowls, cups, cutlery, household silver, plates, plaques, sculpture and jewellery from silver sheet. Silver is a soft metal and easily worked with hand tools such as snips, saws, files, hammers, and a blowpipe or torch for heating the silver. A small hearth would also be needed for casting small shapes which could be soldered together to form more intricate work. Construction involves cutting sheet silver via snips and hammered into shape over anvils. Normally silver is worked cold and the process of hammering has the effect of ‘work-hardening’ the material to a point where it can crack so periodic heat-treatment called annealing is performed to relax the silver and allow further working. Silversmiths are required to hallmark their products and as part of the process register their maker’s mark at the assay office. The fruit knife had hallmarks on the blade identifying the maker as John Bell of Sheffield who manufactured the knife in 1854 (SAO, 1911; Higgs, 1916) as shown in figure 1.4.

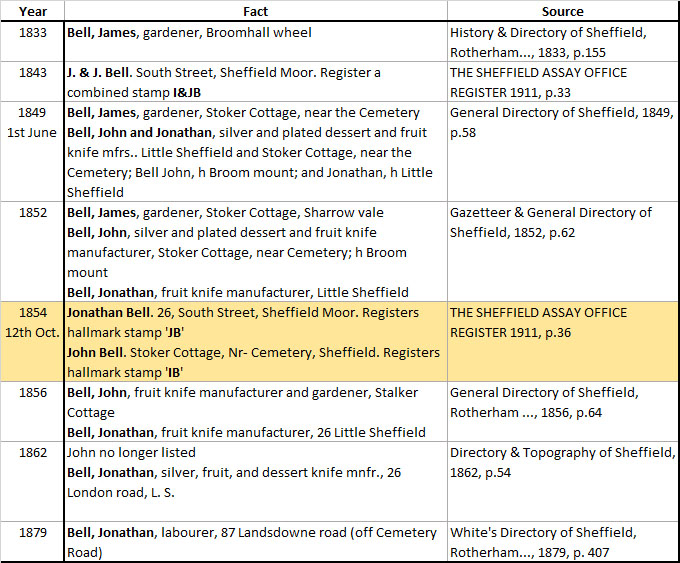

Further research using Trade directories of the time show John Bell’s place of work as Stalker’s Cottage near Cemetery Road (see figure 1.5) and that he worked as a silver and plated dessert and fruit knife manufacturer between 1843 and 1856 possibly through to 1862 as shown in table 1.2.

Sheffield has a long history of metal working and knife manufacture dating as far back as the 14th century and during the Victorian period was widely known throughout the world as producing high quality steel and silver work.

Figure 1.5: Stalker’s Cottage (centre of image) near Cemetery Road, John Bell’s place of work in 1854.

Product

Folding pocketknives have been found from as long ago as 600-500 BCE (Horváth 1987:38-41) and have had various uses and additions made to their feature toolset over the years. The fruit knife was first developed during the 18th century in France but it soon became very popular in England during the 19th century. Victorians thought of them as fashionable and exclusive items and being made of silver were bought as an investment by many. Another reason for their popularity was due to the bad teeth many people, particularly the elite and aristocrats, had and eating fruit such as apples and pears was difficult. The fruit knife allowed for fruit to be easily carved into small pieces and easily consumed. Sterling silver and mother of pearl were ideal materials for fruit knives as they are resistant to citric acid which would corrode other materials including stainless steel. Silver also has an anti-microbial quality which kills bacteria making it a more hygienic alternative to other materials of the period.

Consumption and Exchange

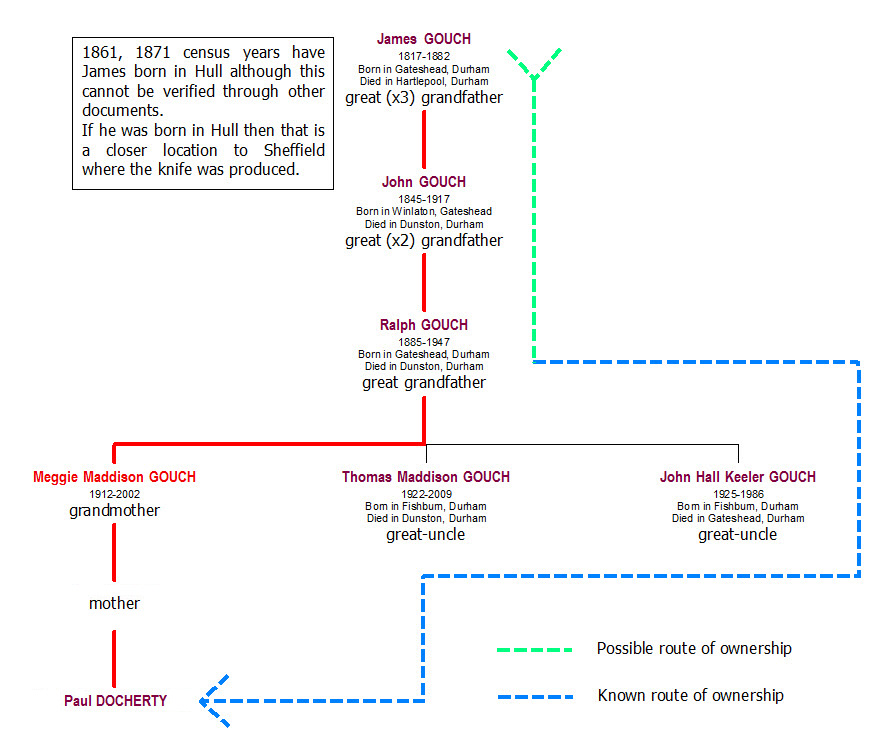

Although originally obtained and used for eating fruit, the knife has been handed down as an heirloom for at least 100 years. It was used to eat fruit up until the 1980’s when it was passed on to Thomas Gouch. The chain of custody is presented in figure 1.6. The family had never been wealthy so this was also thought of as an investment and not just a working knife. Presently its worth is far more important as an heirloom and represents a spiritual connection with previous family members to have held it.

Figure 1.6: Chain of custody for the Fruit knife (Source: Docherty family documents).

Biographical Update

Unfortunately after the original biography was written the knife was damaged in a fire. An update is pending and will appear here in due course.

Bibliography

IAE (2016) Interpreting Archaeological Evidence: Material Culture and Environment (BA Module AR2554 course reader). Leicester: University of Leicester.

Higgs, P. J. (1916) Assay hall marks on old English silver: fourth article. Arts & Decoration (1910-1918), 6 (5), pp. 234-236.

Kovács, T., and Horváth, L. (1987). ‘Transdanubia I’, Corpus of Celtic finds in Hungary. Vol. 1, Budapest: Akademiai Kiado. pp. 38–41.

SAO Sheffield Assay Office (1911) The Sheffield Assay Office Register: A copy of the register of the persons concerned in the manufacture of silver wares, and of the marks entered by them from 1773 to 1907. Sheffield: Sheffield Assay Office.